Of Human Bondage

Fiction 2018. 1. 1. 17:27 |Of Human Bondage

by W. Somerset Maugham

“He did not care if she was heartless, vicious and vulgar, stupid and grasping, he loved her. He would rather have misery with one than happiness with the other.”

“This love was a torment, and he resented bitterly the subjugation in which it held him; he was a prisoner and he longed for freedom.

Sometimes he awoke in the morning and felt nothing; his soul leaped, for he thought he was free; he loved no longer; but in a little while, as he grew wide awake, the pain settled in his heart, and he knew that he was not cured yet.”

“It is an illusion that youth is happy, an illusion of those who have lost it; but the young know they are wretched for they are full of the truthless ideal which have been instilled into them, and each time they come in contact with the real, they are bruised and wounded. It looks as if they were victims of a conspiracy; for the books they read, ideal by the necessity of selection, and the conversation of their elders, who look back upon the past through a rosy haze of forgetfulness, prepare them for an unreal life. They must discover for themselves that all they have read and all they have been told are lies, lies, lies; and each discovery is another nail driven into the body on the cross of life.”

“Oh, it's always the same,' she sighed, 'if you want men to behave well to you, you must be beastly to them; if you treat them decently they make you suffer for it.”

“There's always one who loves and one who lets himself be loved.”

“It was one of the queer things of life that you saw a person every day for months and were so intimate with him that you could not imagine existence without him; then separation came, and everything went on in the same way, and the companion who had seemed essential proved unnecessary.”

“You will find as you grow older that the first thing needful to make the world a tolerable place to live in is to recognize the inevitable selfishness of humanity. You demand unselfishness from others, which is a preposterous claim that they should sacrifice their desires to yours. Why should they? When you are reconciled to the fact that each is for himself in the world you will ask less from your fellows. They will not disappoint you, and you will look upon them more charitably. Men seek but one thing in life -- their pleasure.”

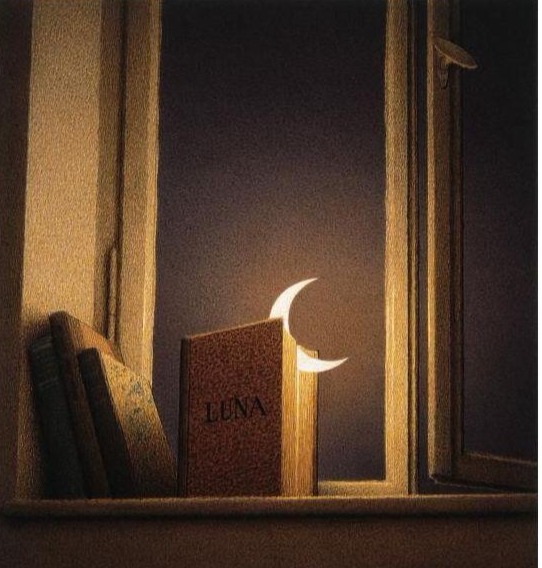

“Insensibly he formed the most delightful habit in the world, the habit of reading: he did not know that thus he was providing himself with a refuge from all the distress of life; he did not know either that he was creating for himself an unreal world which would make the real world of every day a source of bitter disappointment.”

“It's no use crying over spilt milk, because all of the forces of the universe were bent on spilling it.”

“I have nothing but contempt for the people who despise money. They are hypocrites or fools. Money is like a sixth sense without which you cannot make a complete use of the other five. Without an adequate income half the possibilities of life are shut off. The only thing to be careful about is that you do not pay more than a shilling for the shilling you earn. You will hear people say that poverty is the best spur to the artist. They have never felt the iron of it in their flesh. They do not know how mean it makes you. It exposes you to endless humiliation, it cuts your wings, it eats into your soul like a cancer.”

“I’m not afraid of my fear. It’s folly, the Christian argument that you should live always in view of your death. The only way to live is to forget that you’re going to die. Death is unimportant. The fear of it should never influence a single action of the wise man. I know that I shall die struggling for breath, and I know that I shall be horribly afraid. I know that I shall not be able to keep myself from regretting bitterly the life that has brought me to such a pass; but I disown that regret. I now, weak, old, diseased, poor, dying, hold still my soul in my hands, and I regret nothing.”

“From old habit, unconsciously he thanked God that he no longer believed in Him.”

“There was no meaning in life, and man by living served no end. It was immaterial whether he was born or not born, whether he lived or ceased to live. Life was insignificant and death without consequence. Philip exulted, as he had exulted in his boyhood when the weight of a belief in God was lifted from his shoulders: it seemed to him that the last burden of responsibility was taken from him; and for the first time he was utterly free. His insignificance was turned to power, and he felt himself suddenly equal with the cruel fate which had seemed to persecute him; for, if life was meaningless, the world was robbed of its cruelty. What he did or left undone did not matter. Failure was unimportant and success amounted to nothing. He was the most inconsiderate creature in that swarming mass of mankind which for a brief space occupied the surface of the earth; and he was almighty because he had wrenched from chaos the secret of its nothingness. Thoughts came tumbling over one another in Philip's eager fancy, and he took long breaths of joyous satisfaction. He felt inclined to leap and sing. He had not been so happy for months.

'Oh, life,' he cried in his heart, 'Oh life, where is thy sting?”

“Kant thought things, not because they were true, but because he was Kant.”

“It might be that to surrender to happiness was to accept defeat, but it was a defeat better than many victories.”

“He was always seeking for a meaning in life, and here it seemed to him that a meaning was offered; but it was obscure and vague . . . He saw what looked like the truth as by flashes of lightening on a dark, stormy night you might see a mountain range. He seemed to see that a man need not leave his life to chance, but that his will was powerful; he seemed to see that self-control might be as passionate and as active as the surrender to passion; he seemed to see that the inward life might be as manifold, as varied, as rich with experience, as the life of one who conquered realms and explored unknown lands.”

“I don't see the use of reading the same thing over and over again,' said Phillip. 'That's only a laborious form of idleness.'

But are you under the impression that you have so great a mind that you can understand the most profound writer at a first reading?'

I don't want to understand him, I'm not a critic. I'm not interested in him for his sake but for mine.'

Why do you read then?'

Partly for pleasure, because it's a habit and I'm just as uncomfortable if I don't read as if I don't smoke, and partly to know myself. When I read a book I seem to read it with my eyes only, but now and then I come across a passage, perhaps only a phrase, which has a meaning for me, and it becomes part of me; I've got out of the book all that's any use to me and I can't get anything more if I read it a dozen times. ...”

“Why did you look at the sunset?'

Philip answered with his mouth full:

Because I was happy.”

“They're a funny lot, suicides. I remember one man who couldn't get any work to do and his wife died, so he pawned his clothes and bought a revolver; but he made a mess of it, he only shot out an eye and he got alright. And then, if you please, with an eye gone and a piece of his face blown away, he came to the conclusion that the world wasn't such a bad place after all, and he lived happily ever afterwards. Thing I've always noticed, people don't commit suicide for love, as you'd expect, that's just a fancy of novelists; they commit suicide because they haven't got any money. I wonder why that is."

"I suppose money's more important than love," suggest Philip.”

“It is pleasure that lurks in the practice of every one of your virtues. Man performs actions because they are good for him, and when they are good for other people as well they are thought virtuous: if he finds pleasure in helping others he is benevolent; if he finds pleasure in working for society he is public-spirited; but it is for your private pleasure that you give twopence to a beggar as much as it is for my private pleasure that I drink another whiskey and soda. I, less of a humbug than you, neither applaud myself for my pleasure nor demand your admiration.”

“But Philip was impatient with himself; he called to mind his idea of the pattern of life: the unhappiness he had suffered was no more than part of a decoration which was elaborate and beautiful; he told himself strenuously that he must accept with gaiety everything, dreariness and excitement, pleasure and pain, because it added to the richness of the design.”

“Then he saw that the normal was the rarest thing in the world. Everyone had some defect, of body or of mind: he thought of all the people he had known (the whole world was like a sick-house, and there was no rhyme or reason in it), he saw a long procession, deformed in body and warped in mind, some with illness of the flesh, weak hearts or weak lungs, and some with illness of the spirit, languor of will, or a craving for liquor. At this moment he could feel a holy compassion for them all. They were the helpless instruments of blind chance. He could pardon Griffiths for his treachery and Mildred for the pain she had caused him. They could not help themselves. The only reasonable thing was to accept the good of men and be patient with their faults. The words of the dying God crossed his memory:

Forgive them, for they know not what they do.”

“He put off the faith of his childhood quite simply, like a cloak that he no longer needed. At first life seemed strange and lonely without the belief which, though he never realized it, had been an unfailing support. He felt like a man who has leaned on a stick and finds himself forced suddenly to walk without assistance. It really seemed as though the days were colder and the nights more solitary. But he was upheld by the excitement; it seemed to make life a more thrilling adventure; and in a little while the stick which he had throw aside, the cloak which had fallen from his shoulders, seemed an intolerable burden of which he had been eased.”

“It looked as though you did not act in a certain way because you thought in a certain way, but rather you thought in a certain way because you were made in a certain way. Truth had nothing to do with it.”

“Philip himself asked desperately what was the use of living at all. It all seemed inane. It was the same with Cronshaw: it was quite unimportant that he had lived; he was dead and forgotten; his life seemed to have served nothing except to give a pushing journalist occasion to write an article in a review. And Philip cried out in his soul:

'What is the use of it?'

"The effort was so incommensurate with the result. The bright hopes of youth had to be paid for at such a bitter price of disillusionment. Pain and disease and unhappiness weighed down the scale so heavily. What did it all mean? He thought of his own life, the high hopes with which he had entered upon it, the limitations which his body forced upon him, his friendlessness, and the lack of affection which had surrounded his youth. He did not know that he had ever done anything but what seemed best to do, and what a cropper he had come! Other men, with no more advantages than he, succeeded, and others again, with many more, failed. It seemed pure chance. The rain fell alike upon the just and upon the unjust, and for nothing was there a why and a wherefore.”

“Art is merely the refuge which the ingenious have invented, when they were supplied with food and women, to escape the tediousness of life.”

“Oh, my dear fellow, if you want to be a gentleman you must give up being an artist. They’ve got nothing to do with one another. You hear of men painting pot-boilers to keep an aged mother – well, it shows they’re excellent sons, but it’s no excuse for bad work. They’re only tradesmen. An artist would let his mother go to the workhouse.”

“I don’t know what it is that makes someone love you, but whatever it is, it’s the only thing that matters, and if it is not there you won’t create it by kindness, or generosity, or anything of that sort.”

“He was thankful not to have to believe in God, for then such a condition of things would be intolerable; one could reconcile oneself to existence only because it was meaningless.”

“Why don’t you give up drinking?”

“Because I don’t choose. It doesn’t matter what a man does if he’s ready to take the consequences. Well, I’m ready to take the consequences. You talk glibly of giving up drinking, but it’s the only thing I’ve got left now. What do you think life would be to me without it? Can you understand the happiness I get out of my absinthe? I yearn for it; and when I drink it I savour every drop, and afterwards I feel my soul swimming in ineffable happiness. It disgusts you. You are a puritan and in your heart you despise sensual pleasures. Sensual pleasures are the most violent and the most exquisite. I am a man blessed with vivid senses, and I have indulged them with all my soul. I have to pay the penalty now, and I am ready to pay.”

“Men have always formed gods in their own image.”

“Follow your inclinations with due regard to the policeman round the corner.”

'Fiction' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Wolf Hall (0) | 2018.01.01 |

|---|---|

| Bring Up the Bodies (0) | 2018.01.01 |

| Loving Frank (0) | 2018.01.01 |

| The Goldfinch (0) | 2018.01.01 |

| A Manual for Cleaning Women (0) | 2018.01.01 |